2. Valériane Venance

On rage, ruffles, and reclaiming the dressed body.

Valériane Venance, of @independantes_de_coeur

https://independantesdecoeur.com/

There’s a funny building in East London—its location I won’t reveal—that feels like an unending maze of creativity. It was there I first met Valériane—I was visiting two friends, Nic and Ben, the jewellery designers behind CC-Steding, and next thing I knew, we were all drinking wine and smoking rollie cigarettes out the window of their studio.

I remember that first meeting, being completely awestruck by the way Val navigates fabric: fluent, instinctive, reverent. Her relationship to cloth is not just technical but emotional, ancestral, knowing. Dressed in her pieces, my femininity becomes a kind of currency—a way to claim and protect my space, my body, my womanhood.

The name of her label says it all, really. It’s borrowed from the infamous 19th-century courtesan Valtesse de la Bigne, who wrote in her will that despite society’s judgement—for being a woman, for being a sex worker—she had always been indépendante de cœur. Independent at heart. Aren’t we all?

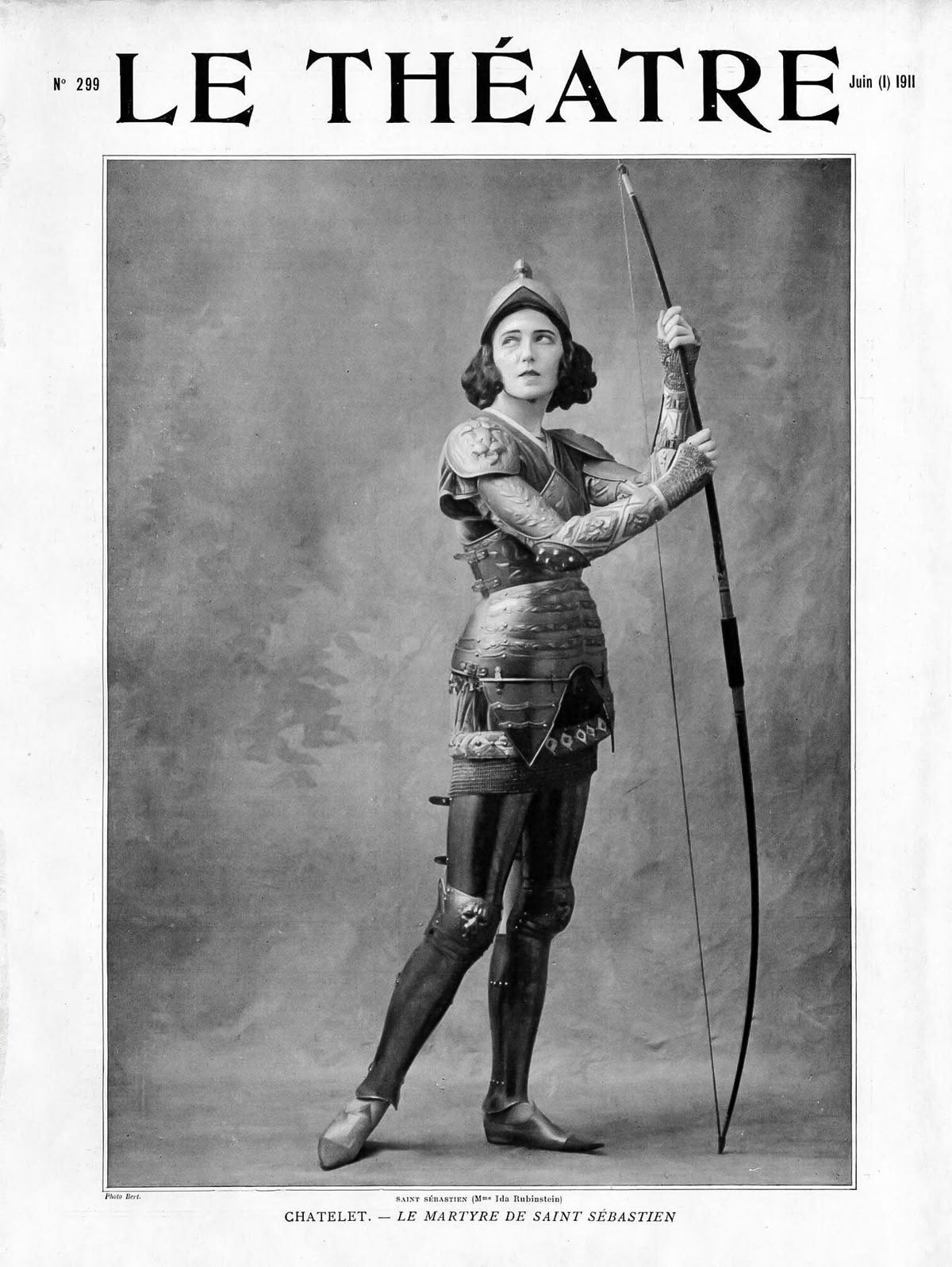

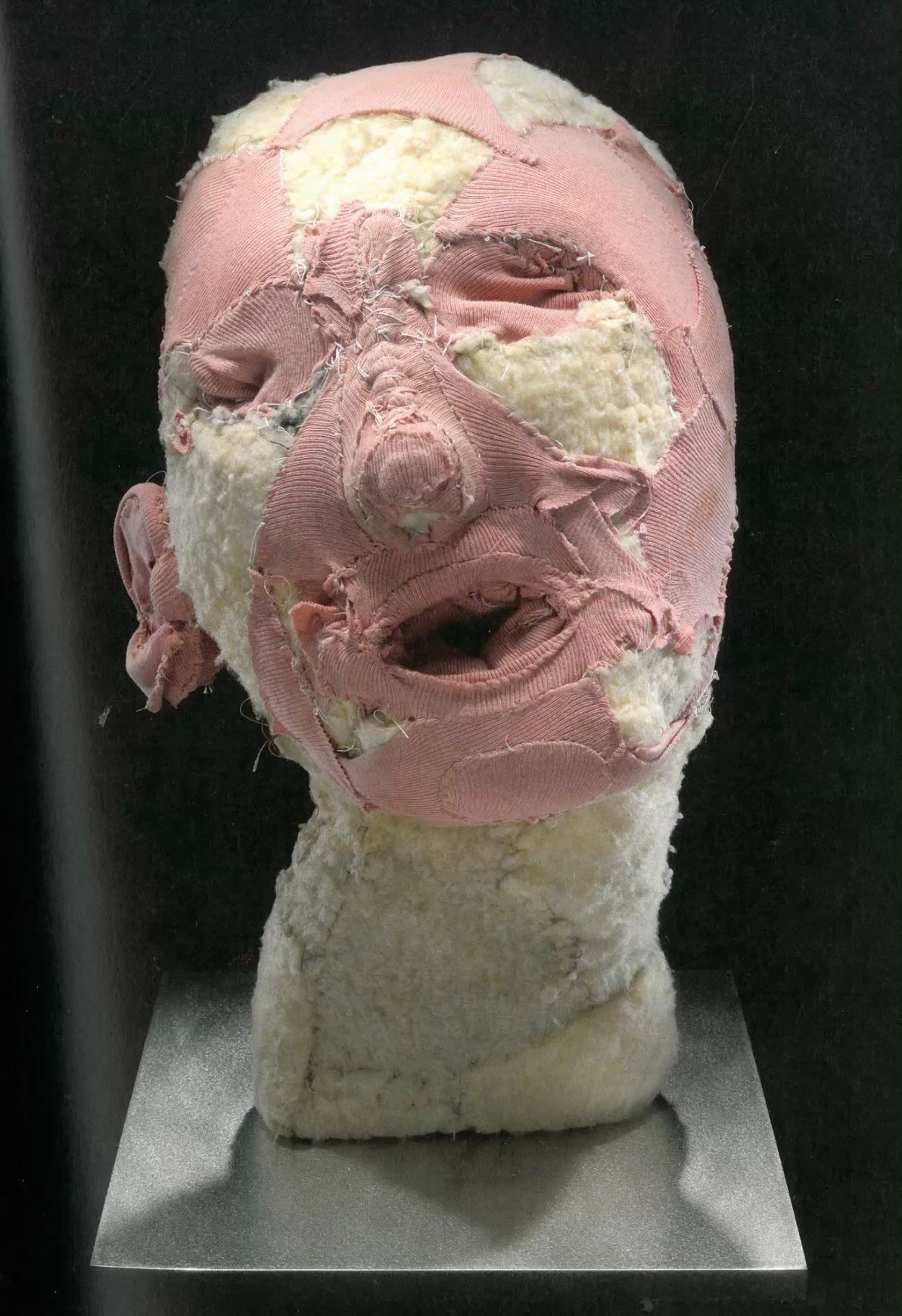

Val is an artist in the way that word should still mean something: fashion is just her tool to digest different disciplines, from music to anthropology to feminism. Beyond her own label, she’s crafted sculptural headpieces for Comme des Garçons, and custom looks for performers like The Horrors, Anohni, and Arca.

If I’ve known Val for several years now, I’d never had the opportunity to dive deep into her creativity—until now. And suddenly, it all makes sense. Dressmaking was her first language; style came before speech; a fluency that has only deepened through the texture of lived experience.

I especially loved her reflections on clothing as a way to claim space and express selfhood as a child—and I encourage you to think about your own. I, for one, used to refuse all the beautiful dresses my mum bought me, insisting instead on wearing a Batman costume. I wonder what that says about me…

Adornment as Primary Language

I grew up in a tiny village in Alsace, in the middle of nowhere basically, tucked in between the mountains and Germany. From my parents’ stories, as soon as I started talking, I was asking my grandmothers to make me dresses. I wanted them to be flat on the top and floaty on the bottom, with little ruffle socks to go with my black patent shoes. And my mum said I was throwing tantrums if my socks didn’t match my dress for school! I have no memory of it, but it makes sense. Marie Antoinette is my birthday buddy—so maybe I’m her fashion reincarnation?

When I was nine or ten, I remember going with my parents to buy clothes at the supermarket. Just, you know, cheap stuff. And I saw this black poncho and a little velvet Gavroche hat that I wanted so badly. My mum bought them for me, but no one at school was wearing anything like it. All the kids were in Adidas and Nike tracksuits. I showed up in my little outfit, and I still remember the effect it had. I was very shy, but people were talking about it. I felt seen, I guess.

Even back then, before I had words for it, I think dressing and style were my first language—without even understanding it was one.

It’s funny because lately I’ve been trying to understand the idea of taste. How it forms through life—what you see, what you hear, the people that surround you. But I also think maybe some part of it was just in me. Because really, where the fuck did it come from? My parents aren’t in any creative field. Not into fashion. Nothing. And I was just obsessed; from the moment I could start dressing—kind of funny enough.

When I was a teenager—my parents divorced when I was eight—I had a stepmother. She hated me, and I hated her. I remember provoking her back then. I must’ve been about fourteen: my dad and my stepmum were invited to a wedding, and I wore the craziest open-back dress—like literally, you could almost see my butt crack. You could see everything, basically.

But I felt untouchable. And it’s a passive act, it’s not an argument or hurling mean words at each other—it’s just something you wear. I actually got refused access to the church, which I was happy about in a cheeky, rebellious teen kind of way.

You have no power when you’re young. I had zero control over this situation that I hated. I think dress was my way to reclaim a little bit of control at an age when so little is.

And maybe that energy is still in the clothes I make now.

Reclaiming the Dressed Body

I remember my grandmother telling me she’d always wanted to go to art school, but her father said it was “only for gays and lesbians.” I was so shocked. She didn’t even get to choose her education—her life. That stuck with me. Now, I always think of freedom: of movement, of choice, of what we can do as women. One of the only ways we can assert to the world that we are free is by doing what we want with our clothing and our bodies—we decide what we show and what we don’t.

My feminism comes from my life’s soup. All the little ingredients: early boyfriends saying, “You can’t wear sneakers, it’s not feminine,” the pressure from everyone about how you should dress, how you should fit in. I remember being a teenager and feeling so angry—like, why can’t I just be myself?

I wanted to go to fashion school in Paris since forever, but my parents didn’t let me. So, I just… went. I applied behind their backs, and when Atelier Chardon Savard called me in for an interview, I hopped on a train without telling anyone. I’d been living out of home since I was fifteen, working various jobs to support myself. I called a nightclub promoter I knew in Paris, said I was bringing my friend Chloé, and crashed at his place. When my dad picked me up from the station, I just said, “I had an interview in Paris.” And that was that.

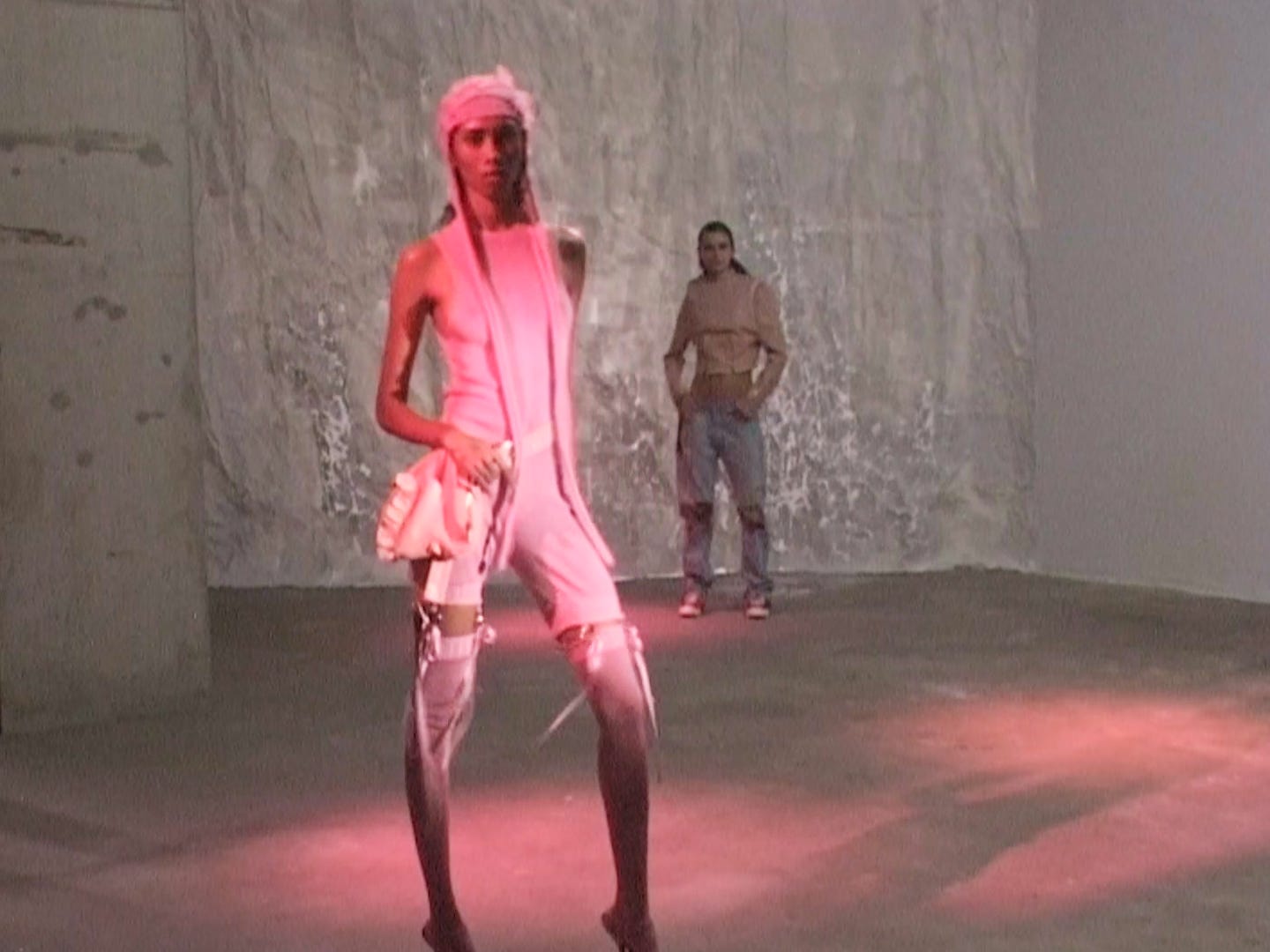

I think it’s become my mission, in a way, to empower women. I have this genuine affection for women—this need to help my fellow women feel their best. To feel confident and untouchable. Like that feeling when you’re listening to a really good song just before a date—that kind of untouchable confidence. I think women should feel that every day.

Something I love is dismantling and reassembling the symbols of femininity—cutting, sculpting, exaggerating. I go through phases myself, sometimes more masculine, sometimes more feminine. That shift between energies—that flexibility—is part of the design too.

There’s so much coming at us from the outside—expectations, judgment, fear. If my clothes can build a small world of beauty and protection around a woman, then that’s everything.

Memory, Material, Meaning

Indépendantes de Coeur happened naturally. I started by making dresses for myself, then for friends. Then people started asking. It just grew. Organically, almost mechanically. There was never a business plan, just a feeling.

I’ve always loved working with antique fabrics—old linens, textured cottons, second-hand bolts I find on the hunt. There’s something so poetic about them. They’ve been stained by time, shaped by hands before mine. They carry weight, history. I like the idea that I’m adding another layer to the story.

But I never make it too literal. I’m not turning a 200-year-old sheet into a Victorian nightgown. I like tension. Something old, sculpted into a sharp, modern silhouette. That’s where the magic happens.

And it’s good for the body too. I’ve read that linen actually vibrates with your body’s frequency. Polyester doesn’t. It’s dead. Linen breathes.

Of course, antique fabric can be tricky—too thick, too fragile. But I wash everything myself, take time with it. And I love offering aftercare, small alterations down the line—if someone’s body changes, or they want to shift a detail. It makes the garment live longer.

There are hard days. Waiting on invoices, wondering if sales will come through. But I’ve learned not to tie success to money. What sustains me is my community—my friends, my collaborators, the people I make for. That’s priceless.

And when things get too much, I just go back to making. No mood board. No deadlines. Just me, sewing something for myself. That’s how I return to the why.

One of my favourite things is the custom work. A performer will come to me and say, “I want to be this character on stage,” and we dream it into being together. It’s like co-creation. I get to study how women see themselves—what they want to show, what they want to hide or enhance. It’s psychological. Even anthropological, sometimes. The clothes are just one part of it.

People always say it’s about empowerment, but honestly, that word gets thrown around so much. For me, it’s more about crafting an emotional armour—but without losing the softness underneath.

If my work contributes anything to fashion, I hope it’s a message of freedom. For women, for art, for anyone trying to feel at home in their own skin.

Val’s words to live by: what else would I do?

( I also have quotes that I leave everywhere. So nice to find in your pockets or laptop or on the studio floor sometimes , my recent one is “Art has always been the raft under which we climb to save our sanity.” Helps me remember the value of the craft, how precious it is, how much beauty you can insert and spread out for other people to feel... How sane it keeps us, all of us!)

Pass it on—3 creatives Val thinks are worth our attention:

Alexia Marmara: painter, archivist, researcher @alexia.marmara

CC-Steding: jewellery makers @ccsteding

Nil Mutluer: culinary masterchef @healgoblin

Pieces I think are worth investing in…

The Kilt: Val’s signature. Elegant with an edge, adjustable for a lifetime of wear, and stitched with a discrete heart on the back; protection, of sorts. Trust me, everyone needs an IDC kilt.

The Convertible Leather Jacket: I’ve worn it myself—the leather is soft like skin, holds shape like armour. Lined in linen, sleeves fastened by a hook and ring. It’s alive; a fierce guardian of spirit and soul.

Merci, dear Valériane, for allowing us to travel through your world, from the past to the now—and for the permission you give us all to dress fully in our power, our selfhood, our dreams.

Thread by thread, these voices are reweaving what fashion can mean across cultures—binding us, artfully, into a global fabric of care. If you enjoyed this interview, consider subscribing—or buy me a coffee—to support more conversations like this.