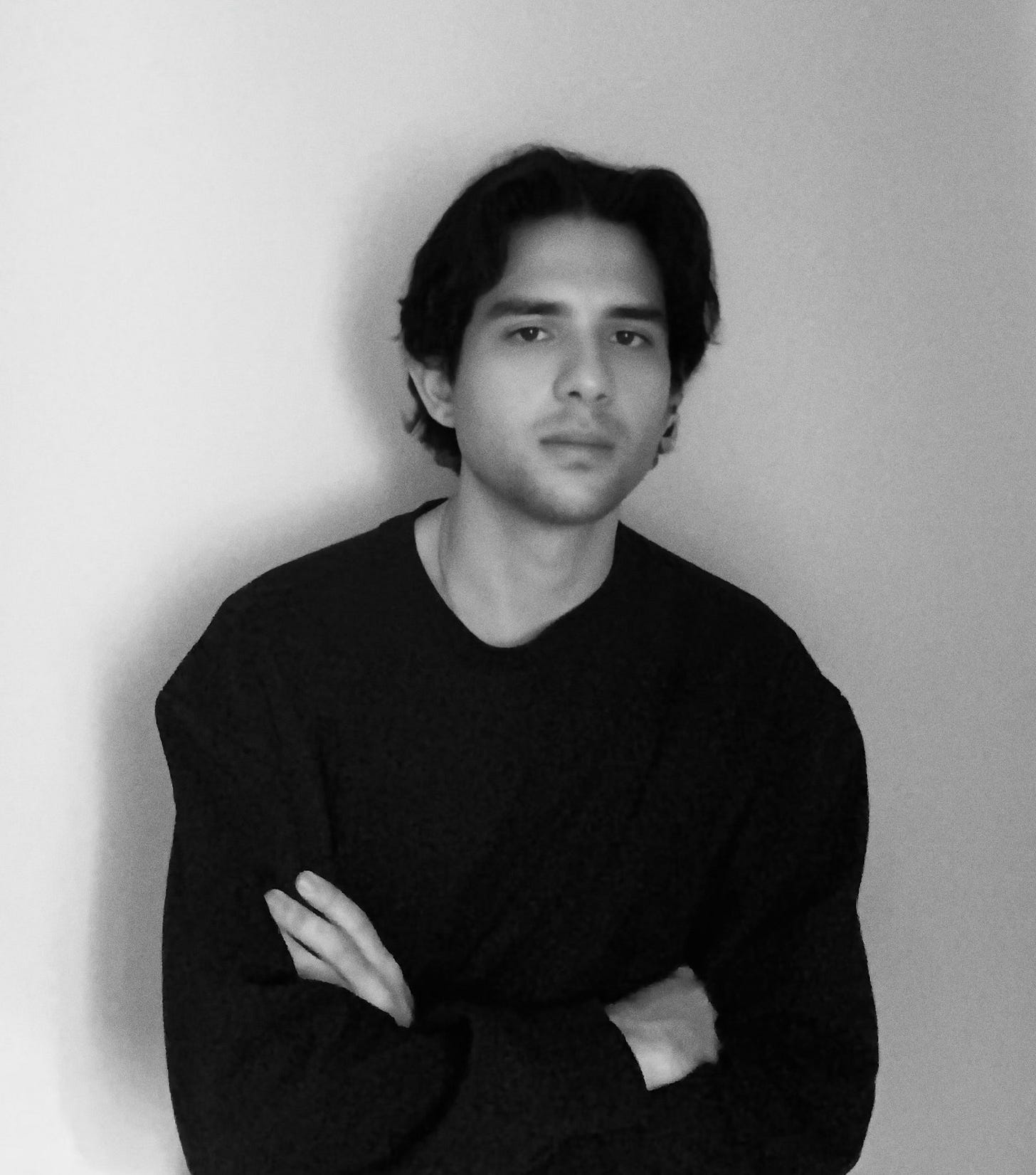

1. Zeid Hijazi

On creativity, crisis, and carrying the ancestral thread

Zeid Hijazi

I first came across designer Zeid Hijazi on Instagram many, many moons ago, and we’ve been in contact ever since. I’ve always had a soft spot for embroidery (how much can be held in a stitch!) and fell immediately in love with his fluency in weaving the traditional craftsmanship of his Palestinian heritage into soulful, contemporary silhouettes—an “Arab futurism,” as he so calls it, with the beauty of the feminine figure as its tether.

A testament to his talent: just two days ago, Rama Duwaji, the wife of the newly elected mayor of NYC, wore one of his designs as her husband, Zohran Mamdani, accepted the win.

When I first started imagining this project, I knew Zeid would be the first person I’d want to interview; I sensed there was a special kind of magic, humility, and spirituality to his story. And I wasn’t wrong. Below, the designer divinely shares his background, his call to fashion, and the mental health struggles that ultimately led him to create from a place guided by something larger than all of us.

As someone who also wrestles with mental health, I so appreciated the safe space that opened between us during this conversation. Those sneaky, dark pockets of my mind felt a little less frightening, and a lot more precious, after speaking with Zeid. And I couldn’t agree with him more: it’s in darkness that we find our inner light—and that sense of self shines brighter than any accolade.

Fashion as Storytelling in the Middle East

I grew up in Jordan, and I was always amused by the power of dressing up. My first real encounter with fashion was through my sister: she was starring in a school play about mannequins coming to life in an atelier at midnight. They started fighting about who looked better, who looked more glamorous. My sister’s mannequin was dressed in the Palestinian thobe, and the others were in these Y2K white outfits. They all made fun of her. But then she had to narrate the story of what she was wearing—and it was like an explosion of colours. I remember thinking, “oh my God, fashion is so cool.”

That moment stayed with me. And of course, watching my mum and my sister dress up had an impact too. In the Middle East, weddings are extravagant—people go all out. I think it’s another story of a kid who grew up watching the women around him and got influenced by it.

Being a fashion designer was always in my head, but I was scared to say it out loud. I was a man, and in our society, there are stereotypes. But when I told my parents, they were really open-minded. They actually sent me to the best school, which I’m very thankful for. I’m 27 now, and I graduated last year. It took me three years to get into Central Saint Martins. The acceptance rate is so low. I didn’t get in the first time, so I took gap years, did short courses, built my portfolio.

There was even this prize for graduates from a new entity and I kind of faked it. I wasn’t a graduate—I’d just done a lot of short courses. But I applied, and I won. That prize helped me release my first collection. Journalists liked it, and I was supposed to go further—to do the second, third, fourth collections—but then everything stopped.

Mental Health, Spiritual Awakening, and the Cost of Creativity

Before my final year, I was doing a lot of weed. It got me into psychosis. That experience changed everything. When you’re creative, it’s like a machine, constantly generating ideas. But when you’re tormented, that machine just stops working. I didn’t release my graduate collection because I didn’t like it. I didn’t feel creative. It triggered a manic episode, then depression. I turned from someone into someone else. I wasn’t myself for years.

I always say it was the best and the worst thing that happened to me. It was such a spiritual experience—it opened me up to bigger things. I became obsessed with the mysteries of the universe. Why are we here? What’s our purpose? Even after the mania ended, my brain was still in a kind of warfare. I had to understand what I’d gone through. It wasn’t just something to “get over.” I mean, suddenly thinking you’re the Second Coming of Jesus Christ—when you know nothing about Jesus Christ—there must be something in that.

Now, thank God, I’m medicated. I’m doing really well. I haven’t had an episode in a long time. But for years, I was more occupied by the spiritual side of what happened than by fashion. I couldn’t release a proper second collection. My dad has offered to support the business—but I’ve been too scared. What if I don’t get any buyers? What if people judge me?

I was really bullied in school, and that stays with you. Even now, when I design, I hear those voices in my head, and I’ll stop for two days. That judgment, that fear, it gets in the way. But I’m doing better now. I’m designing again, I’m doing side projects.

And you know, in fashion, everyone’s anti-taking time off. The pressure is real. But I realised—I have a calling. My desire is to dress women, and to become one of the biggest creative directors in the world. Not from ego, but because it’s my destiny. And to get there, I’ll face challenges that will shape me. They’ll teach me how to handle success when it comes.

Someone once asked me, what kind of support do designers need? Three years ago, I would’ve said mental health. But now I believe mental health struggles are symptoms of something deeper. We’ve lost our spiritual connection. Being spiritual means surrendering to the unknown. When you surrender, your anxiety can start to fade. But we’re afraid to surrender. We’re afraid to look inside.

I’ve been studying Kabbalah, which teaches that we are light. And the brighter your light, the more energy it can attract. But if your light is dim, you won’t receive much. Instead of worrying about turnover and revenue, we should care about what’s going on inside.

Palestinian Identity as Lineage, Not Aesthetic

Yes, I’m Palestinian. And I get so much pressure to make everything about that. But here’s the thing—sometimes I just want to make a sexy dress. Or a really well-tailored blazer. That doesn’t mean I’m not Palestinian. I am. But it’s in my blood. In my trauma. In my ancestry. It’s not a flag I perform.

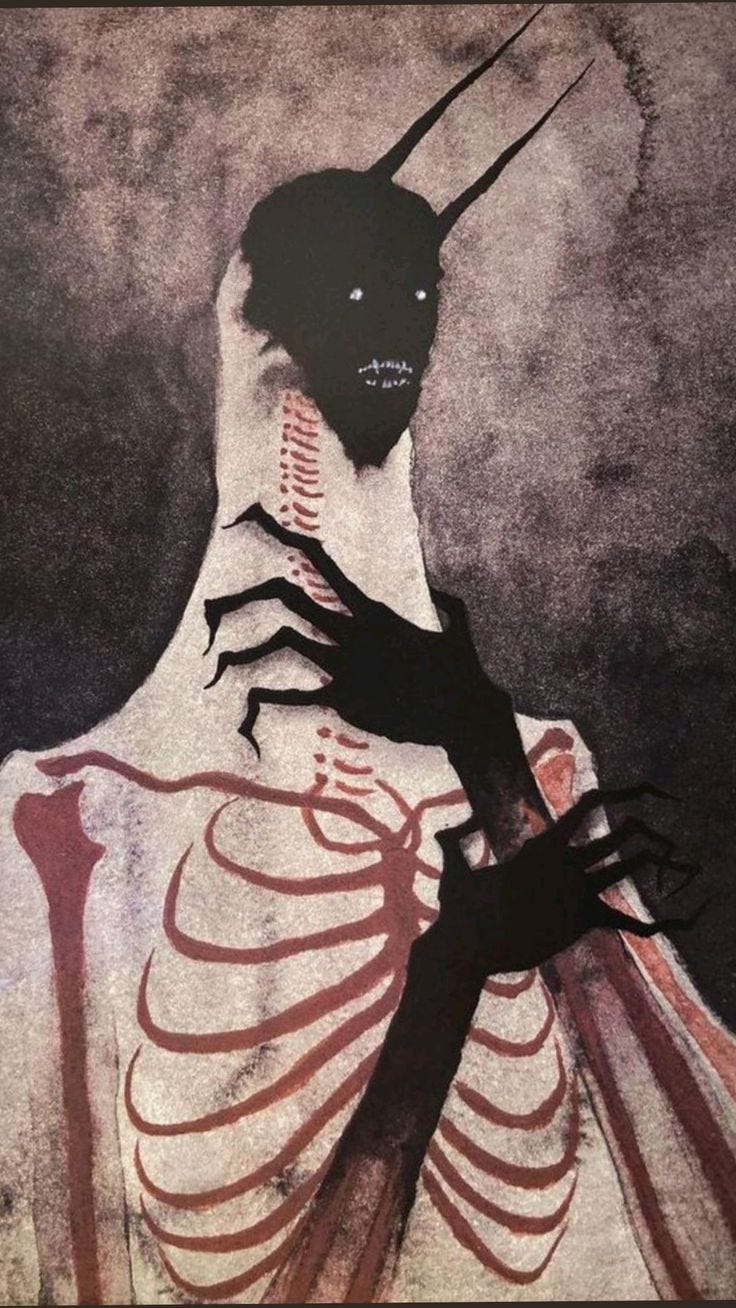

My work comes from a deep place. The collection I’m working on now is called Knightmare—with a K, like “knight.” It’s about going into your subconscious, facing a tormented soul, fighting your inner demons. And a lot of that torment comes from intergenerational trauma. What my ancestors went through—occupation, displacement—it shows up in me. It might be mental illness, it might be autoimmune disease, but it’s in the bloodline.

That’s why I use embroidery. It’s not just aesthetic, it’s storytelling. When a woman puts that needle into fabric, she’s giving birth to something. That soul stays in the garment. That’s identity, memory. My ancestors passed that knowledge down generation to generation. The embroidery becomes like a holy book; it holds ancient wisdom and it preserves our history.

And when someone wears that piece, they insert their own story. It becomes theirs too.

I hate fast fashion—not just because of labour exploitation, but because there’s no soul in it. Those clothes are hollow. I believe every garment should be a vessel for memory. A way to love yourself. Because when a woman puts something on and feels good, it changes her energy. It raises her vibration. And when you love yourself, you attract better things.

That’s what I want to do. That’s how I give love.

Zeid’s words to live by: “Nothing changes if nothing changes.”

Pass it on—3 creatives Zeid thinks are worth our attention:

Cynthia Merhej, of Renaissance Renaissance @renaissance_renaissance

Sabreen Hassan, CSM classmate and super talented CSM designer

Andrew Demetry, Founder of @nafs.space @drew.demetry

Pieces I think are worth investing in…

The Frequency Top (worn by Rama Duwaji): laser-cut denim embroidered with signature motifs, created using a low-impact technique that forgoes harmful dyes and minimises water waste.

The Temple Pants: impeccably cut in raw cotton, with intricate embroidery delicately hand-stitched by Palestinian craftswomen in Jordan.

Thank you, Zeid, for so generously sharing your story—and for offering us each clear-eyed wisdom, soft guidance, and embodied inspiration for our own creative journeys.

Thread by thread, these voices are reweaving what fashion can mean across cultures—binding us, artfully, into a global fabric of care. If you enjoyed this interview, consider subscribing—or buy me a coffee—to support more conversations like this.